The New York City Center, originally known as Mecca Temple, is an unusual theatre with an unusual history. Mecca Temple has the singular distinction of being the only theatre to open its doors with an unpainted auditorium.

Like the Atlanta Fox (drawings, click here) and the Richmond, Va. Mosque (drawings, click here), Mecca Temple was built by the Shriners, but when Mecca opened amidst whirling dervishes and zikers, the auditorium was unpainted.

Two million, five-hundred thousand dollars they spent...

...and the auditorium was as naked as a jaybird.

|

| "Architecture and Building" February 1925 Avery Library |

Mecca was featured in two architectural magazines, the auditorium as white as a sheet.1 American Architect wrote: "At the present time there has been no attempt at color decoration in the auditorium."

The mysterious Shriners explained: "The auditorium will not be completed until next summer. It is impossible to put on the colors." No explanation was forthcoming as to why no other building had this problem. (Complete articles from The Meccan can be viewed here.)

Scarcely ten months after being officially dedicated, Mecca was re-dedicated, this time with John Philip Sousa at the helm.

Triumphantly, the theatre was now in living color, as these black and white studies attest. The full color painting was by L.S. Fischl & Sons whose other jobs included the Hampshire House, Pierre, and Sherry-Netherland Hotels.2

|

| New York Public Library White Studio Collection |

The dazzling proscenium arch, valance, footlights, and what appears to be a tableau curtain, similar to the main drape in the Metropolitan Opera House.

|

| New York Public Library White Studio Collection |

Above the proscenium was emblazoned the inscription Es Selamu Aleikum which according to Shriners International means "Peace be with you."

|

| New York Public Library White Studio Collection |

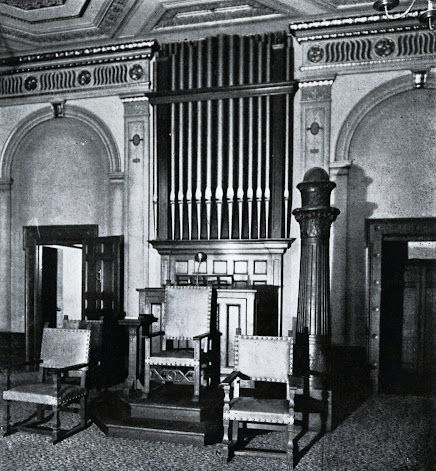

In the early program books, the lower balcony was designated "Dress Circle" and the upper "Balcony" or "Gallery" in the drawings. Besides a fire-proof projection room, "a pipe organ [console] is to be installed in the center of the second gallery." No photographs of this unusual installation have been found, but the specification exists for what the Organ Historical Society Pipe Organ Database describes as a Moller 4/37 which was not completed until mid-1924. The pipes were located in a chamber above the proscenium arch

|

| New York Public Library White Studio Collection |

The Shriners were founded in 1872 by New York actor William Florence (right), and Mecca Temple was the parent of the Shrine. Each chapter or body was given a discrete name, such as Richmond's Acca, Atlanta's Yaarab, and Manhattan's Mecca. Shriners were Masons, but Masons were not necessarily Shriners.

Plans for the new Temple had been announced in 1921 when the membership was 12,000 strong. "We have 11,080 members," said Temple Recorder Louis Donnatin, "and it is apparent that the cost of the mosque when pro-rated among this number represents an insignificant sum." Famous last words.3

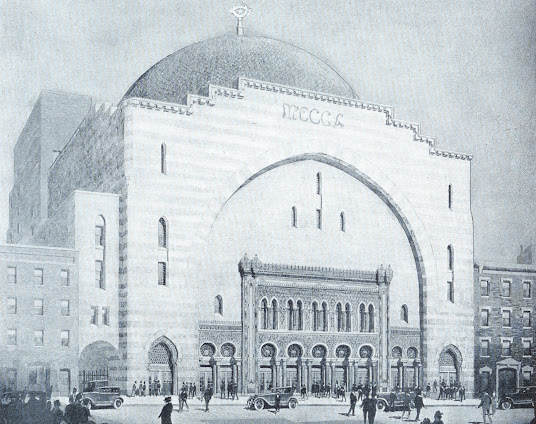

The first published incarnation of the proposed Mecca Temple (rendering courtesy the Livingston Masonic Library) included an opulent twelve-story office building "of Oriental design" and was estimated to cost only $750,000. Other press accounts held to the $2 million figure. "We want an auditorium that will meet the demands of the members. We will have not only an auditorium with a suitable capacity, but we will have smoking rooms, a banquet hall, committee rooms, executive offices, club rooms, and a limited number of rooms for visiting Shriners," explained the Recorder of the Temple.4

The auditorium building bore a passing resemblance to the Hagia Sophia Grand Mosque in Istanbul, a long way from West Fifty-fifth Street.

Unfortunately, Mecca's architect (and Shriner) Harry P. Knowles dropped dead on New Year's Day 1923, long before the start of construction.

Appearing in the October, 1923 issue of The Meccan, a revised architect's rendering relegated the office building to West 56th Street and the auditorium building took center stage. "An immense red-tiled dome, surmounted by the symbolic scimitar and crescent, covers the main auditorium which can seat nearly 5,000 persons," noted the Brooklyn Eagle. The cornerstone was laid on October 13th.5

As seen in this longitudinal section, the main building also contained a high-ceilinged banquet hall down under the auditorium "with room at the tables for 1,000 persons, and with buffet service, the number capable of being served will be trebled," wrote the sometimes mysterious Meccan. "Embodying the last word in steel construction, the main girder in the new Temple is largest steel girder ever used in this city and weighs sixty-five tons," noted The Meccan, although the location and purpose of said girder was not specified.

Beyond the dome can be seen Mecca Temple's non-Oriental office tower, which faced onto West 56th Street. The other occupant of the skyline (to the far right) is the Heckscher (Crown) Building, two blocks north of the Plaza.

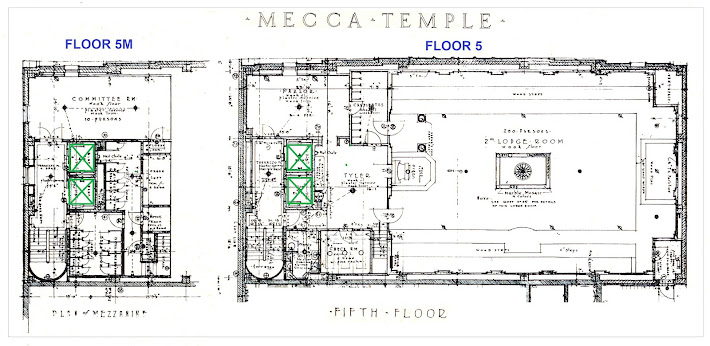

As seen from West 56th Street, the thirteen story office tower contained three double-story Lodge Rooms, executive offices, living quarters, and a roof garden. Two spacious passengers elevators ran all the way from the basement kitchens up to the roof, and for seventy-five years the lifts were non-automatic. The friendly question "What flo' you wan'?" was asked a hundred times a day.

A continuation of the above plan of office building floor 5, separated by a firewall from the adjacent gridiron, the organ chamber, and floor 6 (top) of the dressing room tower. The dressing room elevator is marked in green and the boiler chimney in red.

|

| "The Meccan" October 1923 |

As seen in this longitudinal section, the main building also contained a high-ceilinged banquet hall down under the auditorium "with room at the tables for 1,000 persons, and with buffet service, the number capable of being served will be trebled," wrote the sometimes mysterious Meccan. "Embodying the last word in steel construction, the main girder in the new Temple is largest steel girder ever used in this city and weighs sixty-five tons," noted The Meccan, although the location and purpose of said girder was not specified.

|

| "American Architect" February 1925, University of Chicago |

Beyond the dome can be seen Mecca Temple's non-Oriental office tower, which faced onto West 56th Street. The other occupant of the skyline (to the far right) is the Heckscher (Crown) Building, two blocks north of the Plaza.

|

| "American Architect" February 1925, University of Chicago |

As seen from West 56th Street, the thirteen story office tower contained three double-story Lodge Rooms, executive offices, living quarters, and a roof garden. Two spacious passengers elevators ran all the way from the basement kitchens up to the roof, and for seventy-five years the lifts were non-automatic. The friendly question "What flo' you wan'?" was asked a hundred times a day.

Each Lodge Room could accommodate 200 and contained its own two manual Moller pipe organ and a mezzanine floor for robing. The Blackstone Room's Moller is shown here.

|

| "Architecture and Building" Avery Library |

Below, the West Fifty-sixth Street entries, from east to west. The east entry provided access to the stage door, served as a fire lane from the east auditorium exits, and also provided access to the basement boiler room and Banquet Hall kitchens. "At the west end is a ramp leading to the stage which will permit automobiles or animals to be taken directly to the stage on an incline instead of by elevator," wrote The Meccan. The west auditorium exits dumped onto West Fifty-fifth Street, and originally no shortcut was provided between Fifty-fifth and Fifty-sixth Street.

Below, a plan of the backstage and West Fifty-sixth Street entries. Besides the two office building elevators, a third car serviced the dressing rooms exclusively (in green). "There are two complete sets of dressing rooms," wrote the Richmond Times-Dispatch, "one for the accommodation of theatrical companies and another for the uses of Temple nobles, members, divans, patrols, etc." From The Meccan: "The special rooms planned for the [Shrine] units, our storage and property rooms, are an integral part of the theatre proper, and yet they can be shut off when the theatre is devoted to outside enterprises, and our property will be safe from the transfer men moving a show in or out."6

Plan of the stage and dressing room tower. "An elevator (green rectangle) will permit the lowering of the heaviest automobile truck to the the level of the banquet hall, well below the level of the trap room," wrote The Meccan. "It may be that an automobile show may be held here. [The elevator] will also aid in the presentation of huge spectacles and facilitate the handling of the stunts which can be made ready in the trap room and at the proper time run up to the stage. The ramp to the street and this elevator will simplify the handling of materials in any part of the building, for it will communicate with the kitchens, thought they have a separate entrance for supplies."

The counterweight system and presumably the stage elevator as well were installed by Peter Clark, Inc. and topped the list of their Masonic and Shrine efforts.

a%20first%20floor%20LETTER.jpg) |

| "Architecture and Building" Avery Library |

Plan of the stage and dressing room tower. "An elevator (green rectangle) will permit the lowering of the heaviest automobile truck to the the level of the banquet hall, well below the level of the trap room," wrote The Meccan. "It may be that an automobile show may be held here. [The elevator] will also aid in the presentation of huge spectacles and facilitate the handling of the stunts which can be made ready in the trap room and at the proper time run up to the stage. The ramp to the street and this elevator will simplify the handling of materials in any part of the building, for it will communicate with the kitchens, thought they have a separate entrance for supplies."

The counterweight system and presumably the stage elevator as well were installed by Peter Clark, Inc. and topped the list of their Masonic and Shrine efforts.

According to the 1949 ATPAM touring guide, City Center was outfitted with eighty-seven linesets.

A construction shot of Mecca taken July 18, 1924, its name carved in stone at the apex of the facade.

|

| "American Architect" University of Chicago |

A closer view of the red-tiled dome. Besides being ornamental, the dome contained the auditorium air handlers. Beyond the dome can be seen the location of Mecca's roof garden.

|

| "American Architect" University of Chicago |

|

| NYCAGO.com |

A view showing the twin carriage call signs.

|

| "Architecture and Building" Avery Library |

When disembarking from their carriages (or chauffeur-driven automobiles), patrons would be given a numbered carriage card. At the end of a performance, the carriage call signs would flash a number, and the designated carriage would pull up.

Mecca's ticket lobby with gleaming brass standards and an array of boiling hot radiators.

|

| New York Public Library White Studio Collection |

Directly above the ticket lobby was the mezzanine lounge which sported most of the 55th Street windows.

|

| New York Public Library White Studio Collection |

Mecca's first dedication ceremony, December 29th, 1924, from the Brooklyn Daily Times.

If there were any quibbles about Mecca, one would be the lack of stage wing space-- about five feet on stage right and seven on left. "Stagehands often had to 'catch' dancers as they leapt offstage to keep them from crashing into the wall," recalls senior IATSE man George Dummitt.

|

| "American Architect" University of Chicago |

The greater problem with Mecca was the Shriners' odd decision to specify a "flat oak floor" for the orchestra seating area, instead of pitching it. According to a 1925 article, "the main floor has movable opera chairs, so that it can be used for dancing." A photographic closeup reveals that in fact the orchestra seating for the first season (January through May, 1925) consisted of wooden folding chairs.7

|

| "Architecture and Building" Avery Library |

Opera seating had been installed by the time of the full color painting job, although a 1941 reference claimed "the chairs were not screwed down to the floor, as required in theatres."8

|

| New York Public Library White Studio Collection |

A compelling reason for the New York Symphony to move its 1925-1926 season of twenty Sunday concerts to Mecca was because of the large seating capacity: 4,000, as reported in the New York Times. Yet the true number was more than a thousand less. Estimates of the total number of seats varied as the years went by from "nearly 5,000," to 4,500, and 4,000 (1924); 3,546 (1925); 3,464 (1941); 2,692 (1944); 3,025 (1949); and 2,934 (1975).9

From the beginning, Mecca encouraged rentals of the auditorium, and besides the New York Symphony, paid events also included political rallies or "smokers." One of Mecca Temple's construction boasts was that its special ventilation equipment allowed for the "unrestricted use of tobacco." As reported in The Meccan, "we can have a political meeting in the afternoon with smoking all over the place and in the evening we could give the auditorium to the Women's Christian Temperance Union, and they would never know the house recently had been blue with smoke." Reported the Miami Tribune, "The auditorium is at times filled the smoke of 4,200 cigars." Below, a 1938 meeting of the Teamsters.

The cigar-smoking Marx Brothers rehearsed their first hit show at Mecca.

Over the first fifty years of it existence, the basement Banquet Hall was rented out for dancing, meetings, and rehearsals, with the last advertised usage for Tito Puente in 1968. The hall was generally known as the City Center Ballroom or the City Center Casino.

Leftist organizations enjoyed the use of the both the auditorium and ballroom, one of the earliest being the 1934 "Soviet Night" and in 1939 Gypsy Rose Lee's "Stars for Spain." At least two ballroom meetings helped land Pete Seeger and Norman Corwin in "Red Channels," the dreaded 1950 broadcast blacklist.

Leftist organizations enjoyed the use of the both the auditorium and ballroom, one of the earliest being the 1934 "Soviet Night" and in 1939 Gypsy Rose Lee's "Stars for Spain." At least two ballroom meetings helped land Pete Seeger and Norman Corwin in "Red Channels," the dreaded 1950 broadcast blacklist.

Beset by financial problems beyond the scope of this article, from 1941 until early 1943 Mecca became known as the Cosmopolitan Opera House. A promised renovation to re-pitch the orchestra floor never happened, but the Cosmo years were notable for Stokowski's NBC Symphony radio broadcasts and recordings, one of which can heard here.

In March, 1943 the idea of "City Center" was first discussed.

The 1943 "renovation" was cursory at best, with patron amenities the priority on an extremely limited wartime budget, according to Miss Dalrymple.

At Jean Dalrymple's suggestion, Harry Friedgut was hired as the first manager of the new operation.

An excerpt from the opening night program, December 11, 1943, including a letter from LaGuardia. "Someday the great arts center will be housed in a magnificent structure," wrote the Mayor, stressing from the get-go that Mecca was merely a temporary solution. (To enlarge, right-click on blue area immediately beneath any image; click again to magnify.)

Over the years, City Center produced many different attractions for children, starting in 1944 with Stokowski's "Christmas Story."

Clockwise from upper left, a student performance given during the second (1944-45) season; (1) tickets being taken amidst gleaming brass; (2) the nose of the un-repainted balcony; (3) the mezzanine lounge with war-time windows blacked out; and (4) a chart showing the first season's splendid attendance.

%20combo.jpg) |

| New York Public Library |

From the start, City Center was a producing house and during the 1940's was responsible for the creation and sustenance of the New York City Opera, the New York City Ballet, and the New York City Symphony. Below, Leonard Bernstein conducting the latter in an auditorium which had not been painted since 1925. To hear a broadcast, click here.

|

| Wikimedia Commons file |

City Center converted the Shriners' office building Lodge Rooms into rehearsal studios, and here is Bernstein rehearsing on the fifth floor, formerly known as the Veda Room.

|

| WNYC.org |

Perhaps the greatest star at City Center was choreographer George Balanchine whose myriad City Center accomplishments included New York's perpetual Christmas tradition of "The Nutcracker," commencing in 1954. The original settings by Horace Armistead featured a Christmas tree "that grew before your eyes" to a height of thirty-five feet.

|

| (Left) Life Magazine (Right) "The Nutcracker" (1958) Internet Archive |

City Opera, under the baton of Julius Rudel, produced scores of new operas including Carlisle Floyd's "Susannah" in 1958. Both City Ballet and City Opera toured extensively, underwritten by City Center.

A lighting plot for the City Opera by Jean Rosenthal. Note the semi-circular cyclorama, typical of Peter Clark rigging installations. This plot and the one beneath it are reproduced from Joel Rubin's book "Theatrical Lighting Practice."

Another Rosenthal plot, this for City Ballet.

Nananne Porcher (POR-SHAY) at the City Center stage manager desk in 1951. "Miss Porcher works at a small microphone and calls out and signals her cues to as many as 21 electricians and stagehands" working beneath her. Hanging behind Miss Porcher is a flyer for TPS, Theatre Production Service, a theatrical supply business which she co-owned with Jean Rosenthal.

Orson Wells and Jean Dalrymple grace the cover of Theatre Arts to publicize his "King Lear," one of Dalrymples many achievements as director of the theatre company division of City Center.

In 1954, producer of television's terribly successful "Your Show of Shows" presented a live, color, 90-minute TV spectacular entitled "City Center." "Max Liebman looked no further than his own backyard to find the setting for this production: New York's City Center houses Liebman's own office and rehearsal halls."

In stark contrast to the glittering new theatres at Lincoln Square, City Center was down at the heels, with primitive air-conditioning that relied on deliveries of ice, stage electrics which dated from 1924, and an auditorium that hadn't been painted in over forty years. The full color paint job with "peeling paint and water leaks" was what Lighting Designer Ken Billington recalls when he was given the opportunity to observe load-ins at City Center, under the tutelage of Peggy Clark. Young Billington received his formal training at the Lester Polakov Studio where Miss Clark moonlighted from Broadway as an instructor.10

"This will put the theater in new shape, in back and in front," continued the article.

According to the Daily News, work didn't commence until a year later, in the summer of 1968 with a planned completion date of September to accommodate the Joffrey Ballet.

On this bare-bones budget, the auditorium was not restored, but white-washed. The only known photo of the new paint job appeared in the Kliegl brochure.

1968 also marked the twenty-fifth anniversary of City Center, whose remarkable achievements were cataloged in the New York Times.

In 1959 ground was broken for Robert Moses' Lincoln Center, which included a "theatre for dance," and the handwriting was on the wall for City Center.

|

| WQXR.org |

By 1965, both the City Opera and the City Ballet had moved uptown to Lincoln Center, abandoning City Center after twenty-two and thirty-five seasons, respectively.

|

| Source: ebay |

In stark contrast to the glittering new theatres at Lincoln Square, City Center was down at the heels, with primitive air-conditioning that relied on deliveries of ice, stage electrics which dated from 1924, and an auditorium that hadn't been painted in over forty years. The full color paint job with "peeling paint and water leaks" was what Lighting Designer Ken Billington recalls when he was given the opportunity to observe load-ins at City Center, under the tutelage of Peggy Clark. Young Billington received his formal training at the Lester Polakov Studio where Miss Clark moonlighted from Broadway as an instructor.10

|

| (Left) New York Public Library (right) Ancestry.com |

The original house switchboard, Jimmy Claffey in the foreground. According to Billington, the house also utilized four 14-plate piano boards, two 1500/3000-watt resistance and two 3600-watt autotransformer, the latter the brainchild of Abe Feder for touring "My Fair Lady" and a rarity in New York because they required alternating current.

In 1967, help came to City Center in the form of capital funding from Mayor Lindsay via his wife Mary, who was a prominent member of Jean Dalrymple's Friends of City Center. That Miss Dalrymple worked behind the scenes to make this happen seems a likely possibility.

|

| Getty Images |

The stage electrical work was detailed in a Kliegl Brothers brochure which stated, "Although working drawings were not completed until mid-May, 1968, the system was completely installed and operating by Labor Day of the same year."

Despite being newly-painted, newly air-conditioned, and with a lighting rig equal to Lincoln Center, suddenly City Center ceased to be a producing house. In January, 1969 a new executive director disbanded the Theatre and Light Opera divisions, the last remaining producing units. "My work had ended," wrote Jean Dalrymple in From the Last Row.

So low on the totem pole had City Center sunk that its twenty-fifth anniversary celebration was held at Lincoln Center. Five years later, in 1974, Mecca came perilously close to being demolished, the victim of its own board chairman, a Lindsay appointee.11

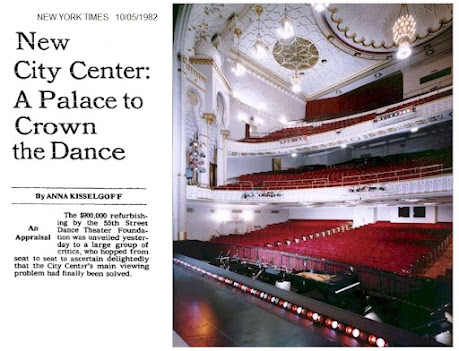

Fortunately, wiser minds prevailed and in 1982 another renovation was undertaken, guided by City Center Executive Director Margaret Wood. The lead architect was Bernard Rothzeid of RKTB, New York.12

The work included a fourth repainting of the house, this time in beige and gold, with nicely disguised circular ceiling diffusers for the air-conditioning. This HD photo, courtesy RKTB, was taken by Robert Lorelli. (To enlarge, right-click on blue area immediately beneath any image; click again to magnify.)

Above the proscenium was the organ chamber, which housed the pipes reportedly removed in 1949 and now playing at a church not near you on West 145th Street.

The work included a fourth repainting of the house, this time in beige and gold, with nicely disguised circular ceiling diffusers for the air-conditioning. This HD photo, courtesy RKTB, was taken by Robert Lorelli. (To enlarge, right-click on blue area immediately beneath any image; click again to magnify.)

|

| Jake Hall photo |

Of equal or greater importance than the new paint job was that the Rothzeid renovation pitched and re-seated the auditorium floor, correcting the problem of fifty-eight years wherein "from the seats in front of Row G, the dancers were invisible from the knees down." Dance critics were unanimous in their praise of the renovation, completed in only twelve weeks.

The next year, 1983, landmark status was granted City Center by New York City's Landmark Preservation Commission, and supporting documents referenced in the application included a history of the building authored by yours truly which can be viewed here. It is also held by the New York Public Library at this address.

In 1984, the air rights to City Center were sold, resulting in a $5 million windfall for further renovations.

The construction of a spacious stage right wing was the first air rights project on the agenda, and work was completed in the summer of 1986, under the supervision of architect RKTB's Bernard Rothzeid and City Center Director Tony Micocci, pictured below.13

The construction of a spacious stage right wing was the first air rights project on the agenda, and work was completed in the summer of 1986, under the supervision of architect RKTB's Bernard Rothzeid and City Center Director Tony Micocci, pictured below.13

|

| Courtesy RKTB, Richard Rodamar photo |

In 1992, Judy Daykin seized the reins, and within two years she had created the Encores! series which put City Center squarely back on the map. From Daykin's first lovingly selected "Fiorello!" City Center was once again a producing house.

That same year Christopher Gray speculated in his weekly Times column "Streetscapes" whether the house would ever be repainted to its former glory, and longtime City Center consulting architect Bernard Rothzeid recalled a rainbow of color from his first visit in 1948.

Rothzeid's firm also supervised substantial upgrades of the two small theatres which had occupied the basement Banquet Hall since 1982 when the Manhattan Theatre Club moved in. Theatre One left, Theatre Two, right.

In 2000, the ghost of TV producer Max Liebman returned when forty-six boxes of scripts from "Your Show of Shows" were found in a sealed closet on 6M, the location of his former offices. |

| Courtesy RKTB, Julian Olivas photos |

|

| "Eyes of a Generation" photo |

In 2011, under the expert direction of Ennead Architects (nee Polshek Partnership), the auditorium at City Center received its fifth coat of paint, and once again Mecca was in full color.14

|

| (Left) "American Architect" University of Chicago, (right) New York Times |

In 1999, Director Daykin produced a City Center memorial for Jean Dalrymple ("the other J.D.") who had gone to to Heaven at the age of 96. Miss Dalrymple recounts her love affair with City Center in a half-hour video interview which can be seen here and which she recorded when she was only eighty-seven.

###

Sources and thanks: Ken Billington (Lighting Designer and Lighting Design Historian) , Rachel Britain (Ennead Architects), John Calhoun (New York Public Library), Bill Counter (Los Angeles Theatre Expert), Jenny B. Davis (Columbia University Avery Architectural Library), Judith Daykin (City Center Executive Director 1992-2003), George Dummitt (former House Carpenter Belasco Theatre), Katherine Olson (University of Chicago Library), Luanne Konopko (RKTB Architects), Jeremy MeGraw (New York Public Library), Tony Micocci (City Center Executive Director 1986-1991), Paul Miller (City Center Lighting Designer 2006-present), James Othuse (Kliegl brochure), Richard Rodamar (photographer), Eric Schultz (City Center Master Electrician 1992-2017), Jim Stettner (Organ Historical Society Pipe Organ Database), Leith ter Muelen (Expert and Friend to all), Lloyd Westerman, and Michael Zande (Company Manager City Center Joffrey Ballet 1981-1986, Company Manager City Center Encores! 1997-2012).

2. "Architecture and Building" credits L.S. Fischl and Sons, their other credits listed in Daily News, 9/09/1955.↩

3. Donnatin quote,Victoria Daily News, 1/18/1922.↩

4. "Of Oriental design," New York Times, 10/14/1923; Donnatin quote, Victoria Daily News, 1/18/1922.↩

5. Brooklyn Eagle, 12/19/1924; "Cornerstone laid" The Meccan↩

6. Richmond Times-Dispatch, 1/04/1925; "The other rooms..." The Meccan.↩

7. "Flat oak floor" First floor drawing in "American Architecture"; "The main floor... "Burlington Free Press, 1/01/1925.↩

8. "Not screwed down..." New York Times, 1/10/1941.↩

9. "Nearly 5,000" New York Times, 9/02/1941; 4,500 Brooklyn Daily News, 12/31/1924; 4,000, Springfield Daily Republican, 3/16/1925; 3.946, Akron Beacon Journal, 10/17/1925; 3,464, Musical Courier, 9/1941; 2,692, New York Times, 3/12/1944; 3,025, 1949 ATPAM Touring Guide; 2,934 "From the Last Row, " Jean Dalrymple. ↩

10. Email interview Ken Billington, November 2024.↩

11. "Held at Lincoln Center," Daily New, 10/18/1968; "a Lindsay appointee," "From the Last Row," Jean Dalrymple. ↩

12. "City Center Renovation Set for Summer," New York Times, 3/16/1982; "A New View at a Renovated City Center," Newsday, 10/05/1982; Robert Lorelli involvement, "Long Islanders; At Center Stage in World of Theatre," New York Times, 10/17/1982; "Turning the City Center Theater into a First-rate Dance Space," New York Times, 8/29/1982.↩

13. "That Skyscraper Over City Center Looms Ever Closer," Daily News, 1/1/1985.↩

14. "City Center to Begin $75 million Renovation," New York Times 3/16/2010; ""Second Act," Newsday, 10/25/2011.↩

To view the Master Index of all of Bob Foreman's photo-essays, click here.

December 2024.

a%20combo%20rev%20numB.jpg)

%20COMBO.jpg)